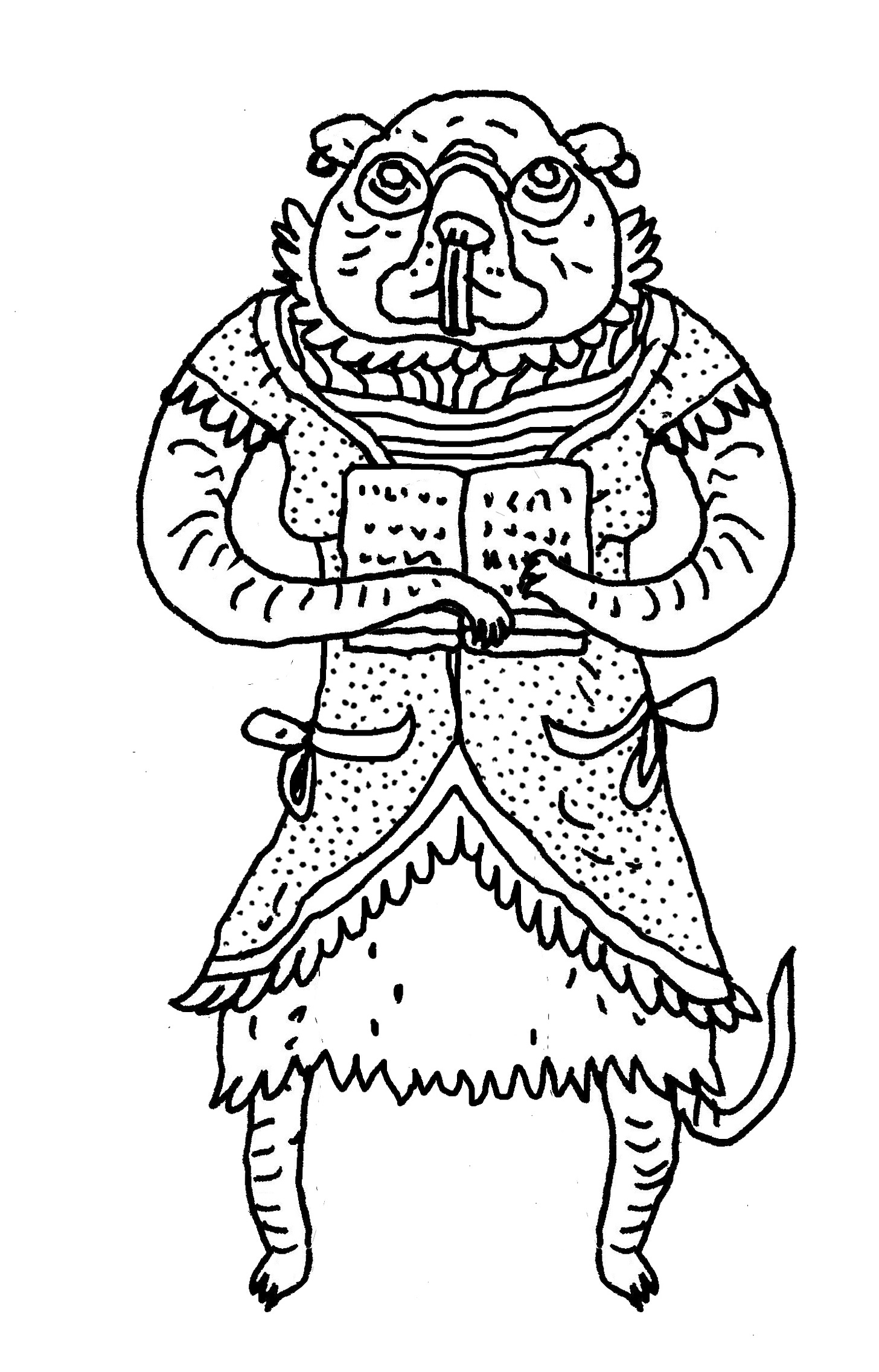

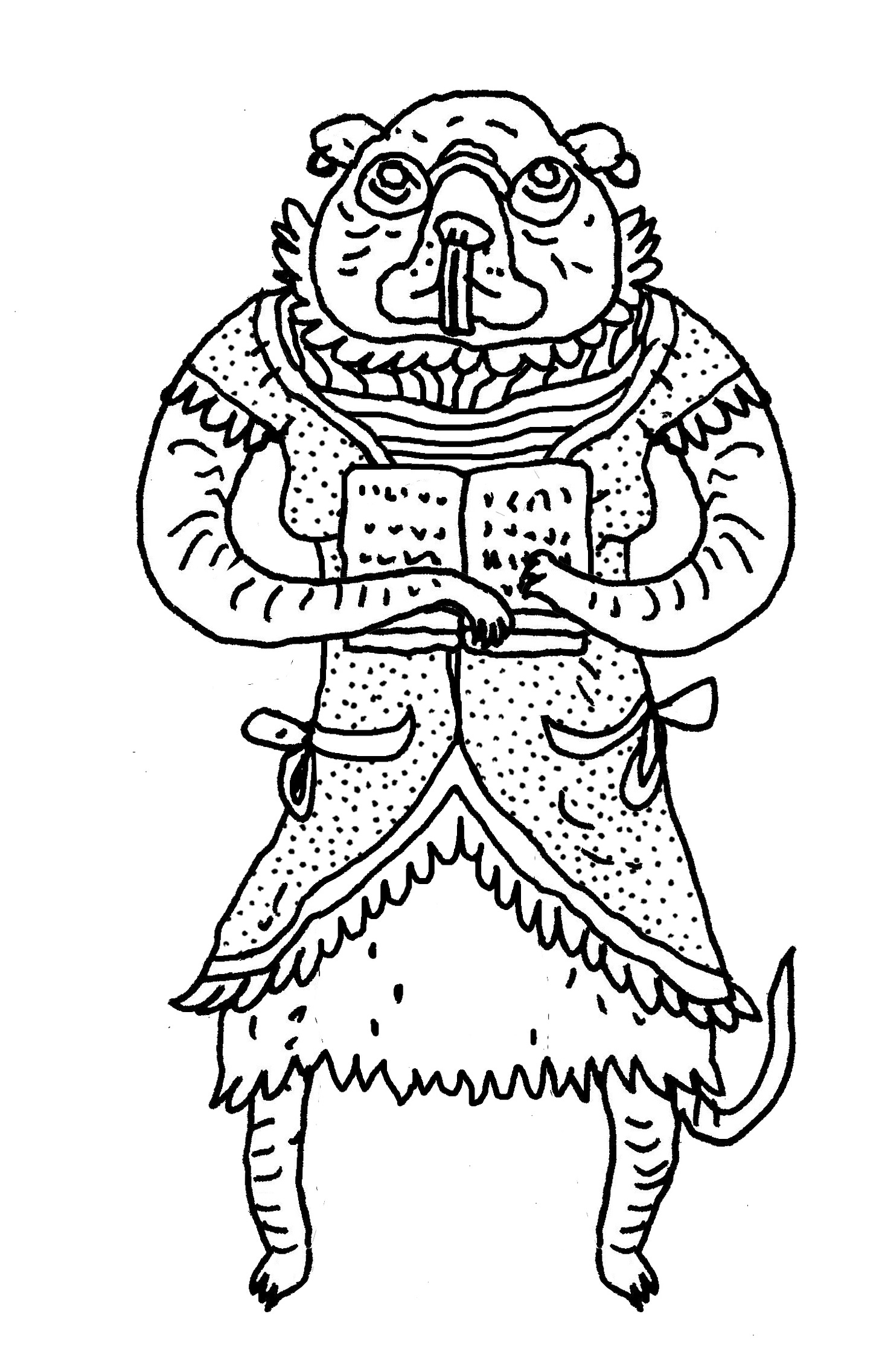

I had some more thoughts on downtime I wanted to share. But first, speaking of downtime, it was just announced that my supplement, Downtime in Zyan, is one of the winners of The Awards 2023! You can check out the full list of winners here. It’s an honor I share with my team. Downtime in Zyan is what it is thanks both to the meticulous layout of Lester B. Portley, and especially to Evlyn Moreau’s superb mole rat illustrations, without which the supplement would be a hollow shell. But back to the topic at hand.

My downtime system is designed to deliver various goods. It serves as an antidote to the relentlessly cooperative and world-focused character of OSR play by allowing PCs to develop some uniqueness and depth. It facilitates the pursuit of individual ends in addition to the collective ones. By not gating downtime behind name level play it allow players to pursue their dreams and leave their mark on the campaign world from early levels. It is also designed to be part of a virtuous circle with adventuring, so that downtime itself creates hooks and problems to be solved through adventuring, and adventuring creates the possibility of further downtime.

Last time I was talking about the problem of the transition in an OSR style campaign between the quick jaunts of early sessions, in and out of perilous adventure locales in 1 or 2 sessions, and the more ambitious many (4-8) session adventures that tend to organically arise starting at mid levels. The thought was that if you have reached the point in the campaign where players adventure for 4+ sessions, and you give players one downtime session every time they return to home base, downtime dwindles in significance. To keep players invested in downtime, I suggested calibrating downtime to the number of sessions adventuring, giving multiple downtimes when returning home after longer adventures.

This time I wanted to talk about a different trick you can use to allow downtime to work with longer jaunts into dangerous territory. The setup I’m thinking of here is one where there is a homebase that is safe where downtime usually happens and most or all adventuring happens in some perilous terra incognita, a hostile area to be explored that lies in some sense “outside” the homebase. A classic example would be a megadungeon, where there is a “town”, and all (or most) adventuring happens in the exploration of the hostile subterranean dungeon. Other examples might include a West Marches style wilderness crawl with a town on the edge of some howling wilderness, or what is on the other side of a certain printmaker’s door in the waking world. In these cases, to penetrate deeper you must often travel further and further from home base, which in turn leads to longer adventures.

One way to limit this problem is to create discoverable shortcuts, e.g. secret doors, hidden elevators in a dungeon, or secret entrances that lead directly into deeper levels. But another way to handle it and keep downtime going is to establish possible basecamps where downtime can happen that also serve as staging areas for deeper exploration. These are, in essence, a home away from home. I’ve been thinking a lot about what you need to do to make this option sing.

Introducing a second space for downtime is a delicate balance. If you design the basecamp so that it provides everything the homebase does, and it is more conveniently located, then your basecamp will predicatably become the campaign’s new homebase. While I think it’s great if this arises organically, I don’t think you want to design the basecamp to force that decision. The biggest problem is that many downtime activities are tied to a location and so not transferable, particularly two of the most important: cultivating relationships and building institutions. It’s unfortunately when some PCs have been sinking time and resources into building something special back at the original homebase and the GM more or less mandates that downtime play shifts to a new arena.

My way of handling this problem is to treat basecamps as scaled down version that presents a smaller world of possibilities than homebases. What you want is enough for people to become invested and pursue downtime while on larger expeditions, while also welcoming the eventual return home to the original homebase.

In fact, there is a spectrum here. At one end, you might have locations in the dungeon or wilderness that offer primarily a single unique downtime action. A couple of options to incorporate in a dungeon might include:

A perpetual feast of viking ghosts in a Valhalla style mead hall that one can join for spectral revelry

A dungeon library, manned by demonic librarians, where can research the kinds of mysteries found in lower levels of the dungeon.

An efreet smithy who uses elemental fires to craft splendid weapons for visitors who can pay his price.

This designs a foothold, a stopover where some may want to do the main downtime action, and others might do an alternative one, like engaging in martial training with a drunken viking ghost, or cultivating a relationship with a demonic librarian, without there being much staying power to the location. At the other end, there are basecamps proper that have real opportunity to build something lasting. How can you build a proper basecamp?

The answer is that you should employ the same techniques you use to build an original homebase, which I talk about at the end of Downtime in Zyan, but give it a more limited and small scale flavor. In brief, since my system of downtime generates problems and adventure hooks with many mixed success rolls it also needs to be a space rife with factions, rival institutions, patrons, in short people with desires and an a potential interest in the PCs adventuring in.the unknown. If we just look at the core of my location specific downtime activities we can see some features we’ll need:

Build an institution: There should be some pre-existing institutions, including perhaps rivalries, along with space for building new institutions.

Cultivate a relationships and Gather Intelligence: There should be interesting NPCs, who have some tensions, and who may want various things that adventurers could provide through adventure, who have access to a rumor mill, and who may be interested in serving as adventuring companions.

Revelry: There should be some possibilities for debauches to blow off steam.

Others downtime actions are either more player driven, or seem more optional, but potential sources of fun might be to include some NPCs that have skills to teach, or some warriors who can engage in martial training, or some special site for spiritual exercises, or a trove of information to engage in research.

To really make a basecamp sing, I think you also need a new version of a campaign events table might used for a homebase, but geared towards the specific nature of the basecamp.

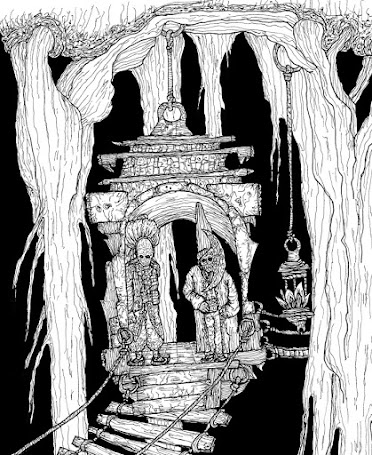

An Example: The Hanging Merchants

|

| Illustration of the Hanging Merchants by Michael Raston |

Each of the four merchants specializes in a different sort of goods. Two of the are over-merchants, from wealthy houses. Each of these over-merchants is locked in bitter rivalry with the other, and each is beholden to a powerful rival jungle patron who will seek the service of any party that uses the area as a basecamp. There are also two under-merchants, with much humbler shops, whom the over merchants look down upon. Finally, there are the Sons and Daughters of the Vigilant Watcher, a mercenary house that the merchants pay to provide protection against jungle incursion and river piracy.

I model the four merchants as four separate rival institutions the players can choose to bolster. (Certainly the Sons and Daughters taken together as a mercenary house are also an institution.) There is also the possibility of trying to open a fifth shop, or more grandly, of trying to restore the platforms of the hanging merchants to their earlier splendor by fixing the place up and attracting visitors. (Each of these two projects was pursued by in separate campaigns by players: one group tried to build up one of the under-merchants, and the other took on the task of restoring the whole place to its former grandeur.) Furthermore there are plenty of NPCs to befriend here, as well as sources of information. Since the Over-merchant are eager to host lavish parties there is the opportunity for revelry as well, and since each under-merchant has a specialty in respectively jungle botany and animal husbandry, there are skills that can be learned as well.

The campaign events for this basecamp includes special goods coming in to the merchants, restocks of sold wears, visitors to the platforms of the merchants from Zyan above, stranger visitors from the jungle below, a couple of jungle related events, and so on.

In short, if you’re doing the kind of campaign where you have a fixed homebase, with all adventuring happening in hostile terrain, consider introducing one or more footholds where downtime can be pursued in the deeper areas of exploration. This can provide variety and keep downtime relevant as the campaign often pushes further from homebase.

.jpeg)