I recently

reviewed John Battle's My Body is a Cage for

Bones of Contention. Battle’s game combines slice of life real world downtime with adventuring in dream dungeons. The game comes with 7 dungeons that embody dream aesthetics quite vividly. I ran the dreamy Hotel Atkinson by Ema Acosta for playtesting purposes. Although the dream aesthetics came through strong in the adventure, there were some downsides that bothered my players. This got me thinking about a dilemma one faces when combining dream aesthetics with the playstyle associated with the OSR. I thought it might be worth saying how I resolve the dilemma in my own published work and home game. I think what I have to say is generally applicable for OSR games.

Dreamlands Aesthetics vs. Dream Aesthetics

When discussing dream aesthetics, I think it’s worth distinguishing two things. The first is the literary tradition of writing about travel in dream worlds. Let us call this the “dreamlands aesthetic”. Although there are no doubt many such traditions, I’m thinking here primarily of weird tales or fantasy authors, most notably Lord Dunsany and H.P. Lovecraft, and their several imitators and elaborators. This is a literary tradition, a special variant of the weird tale, with its own tropes, imaginaries, forms of expression, and aesthetics. In these authors we find the idea of a land of dreams, or the dreamlands, a sort of stable and fantastic country in some way reached through dreams. The authors tend to use both surreal elements and exoticism, sometimes orientalist in its inflection, as a way of emphasizing the fantastical otherness of this place beyond the veil of sleep. We also find many particulars, like the idea in Lovecraft that cats have a special place in the land of dreams, or the idea in Dunsany that one may only cross over to the land of dreams if one knows the hidden places that straddle the two worlds.

We might distinguish this weird tale tradition from what I call “dream aesthetics”. To evoke dream aesthetics is to attempts to create a dreamlike quality by incorporating features of dreams. Dream aesthetics draws on our own nocturnal experience with unstable transitions, surreal and absurd elements, nightmares, anxiety dreams, and so on. Dreamlands fiction, of course, does tap into this surreal wellspring to some extent in its construction of a mysterious and wondrous other country, but it’s far from the dominant theme.

For a literary-visual case that hews far closer to dream aesthetics than Lovecraft or Dunsany, take Winsor McCay’s glorious comic,

Little Nemo in Slumberland. The strip ran as a full pages in the Sunday edition of the

New York Herald from 1905-1911. (It had some later reincarnations in different papers.) In its first two years, each installment was in the form of one of little Nemo’s recurring dream of his failed attempts to reach the princess of slumberland for a playdate at her palace. Each installment ended in anxiety dream fashion, with things getting out of hand in some catastrophic way, only for Nemo to awaken in his bed, tangled in the sheets. Along the way the comic evokes surreal and absurd elements to create a a glorious dreamlike visual experience. The comic is shot through with dream aesthetics, beginning with the use of recurring anxiety dreams to frame the serial, and then the extended of surreal elements like the manner of transit, as in the precarious walking bed in the strip above.

I’ll talk more about dreamlands aesthetics, and Dunsany and Lovecraft, another time (and maybe Windsor McKay too). But for now, I want to turn to the question what happens if we wish to evoke dream aesthetics in our roleplaying games. Can we do for old school roleplaying games what Little Nemo in Slumberland did for Sunday comics?

Dream Aesthetics

Suppose you want to infuse a locale--say a dungeon or pointcrawl—with a dreamlike vibe. Here are some surreal features of actual dreams on which you might be tempted to draw to produce a dream aesthetic for that dungeon.

In dreams, the spatial logic of physical locations breaks down. Places are conflated. Sometimes I'm in one place but it's mysteriously also at the same time another place. Or it's an amalgam of two very different places. There are also sudden transitions between locations. I might open a closet door and find myself on a beach. Dreams are less about navigating objective spaces and more about a vivid sense of place. Generally speaking, coherent spatial representations that links a space you occupy from the first person point of view to an objective map of a region that one is navigating—the sort of thing that looms large in driving apps—does not get a lot of play in our dreams.

Causality is also wonky in dreams. In an anxiety dream, no matter how hard I try, maybe I can't get the key out of the bottom of my backpack, or into the lock; or to my consternation my gun shoots a stream of bubbles instead of bullets at my pursuer. The identity of objects can also get weird. A piece of fruit might somehow also be a book, or a sword a key, or a mirror a disease.

Another way in which dreams are surreal is the people you meet. We find the same mysterious identities here too. For example, someone you know well in real life might look entirely different in the dream, or the person might be an amalgam of two people at once, or a part of a person. Often people we meet in dreams seem less like genuinely intelligent others and more like symbols or figments that occupy a certain role in given scenes. The people we are with often shift subtly as well, without it seeming strange to us in the dream.

OSR Play Styles

In OSR play, player characters

explore perilous and fantastical spaces, seeking to overcome

objective challenges to accomplish their goals. Furthermore, OSR style games are

sandboxes rather than railroads, emphasizing player agency and unpredictable solutions to open-ended problems, as well as emergent rather than scripted stories.

Dungeons, as location-based rather than scene-based adventures, work well in this context provided they are designed with an open-ended spatial logic. The link between the first person point of view and an objective map of space is crucial. Part of the exploration of a dungeon involves uncovering spatial relations between locations in play. You learn that this room is over here in this quadrant, and there is a secret way to get from here to there, or that this region of the dungeon sits atop this other region, which can be accessed vertically through a chasm.

Why is this important to the playstyle? Partly it’s about discovering the unknown—i.e. the pleasure of the players coming to know about things that (already) exist in unexplored regions of the map. But provided the dungeon is properly

Jaquaysed, these coherent spatial discoveries also allow for high levels of player agency and unpredictable interaction. The players can come at locations from different routes. They can leverage their knowledge of a coherent space to short-circuit hazards, sneak past inhabitants, give monsters and NPCs the run-around, use environmental features in unpredictable ways to stage ambushes or solve problems, and so on.

Furthermore, generally speaking, in OSR games, NPCs are parts of

factions that want things and so can be engaged with in social ways. Many old school games start an encounter with a reaction roll that determines the starting disposition of encountered beings. You can ally with one faction against another. You can get an NPC something they want to win them over to your cause. You can tangle with a faction one time and make it up to them later when you have common cause, or when you regret your past actions and try to make amends. In other words, there are fewer “monsters” that are “just there to kill". Some systems don't even give you XP for fighting monsters, or only a pittance. Many systems use morale checks, so monsters or NPCs mainly don't fight to the death. In all these ways that means that many NPCs and dungeon inhabitants need to have intelligible desires and robust lives of their own. They are very much not figments of your imagination, or only part of some weird vignette that you stumble upon in a pre-programmed scene.

When it comes to things it's important that the causality work in the normal way unless there's something special about the thing in question (e.g. magic). In OSR playstyles, since "the answer is (often) not on your character sheet", players tend to rely on what S. John Ross calls

invisible rulebooks, i.e. commonsense knowledge about how things in the environment generally work, in order to engage in lateral problem-solving. This means that guns (so to speak) don't shoot bubbles unless they're magical bubble guns. Similarly, water will generally work like water does. You can't suddenly walk on water just because someone tells you that they believe in you, even if it would make for a vivid dreamlike scene.

The combination of coherent space, determinate factions, and normal causality also allows the GM to avoid arbitrary fiat by reasoning naturalistically about how different factions would respond to player actions. By looking at where they are in relation to what the PCs are doing and what's the factions generally get up to, the GM can reason about what would be likely to happen. This is part of what sustains whatever kernel of truth there is in the idea that the GM is a referee in OSR playstyles. The players trust the GM to set up a situation (say an exploration locale) without having any idea how things are going to go down in play. They also trust the GM to call the shots as they see them. When the PCs brings their chaotic shenanigans into contact with the pre-existing locale, the GM thinks about what would actually happen without stacking the deck one way or another.

The Dream Aesthetics Dilemma

The dream aesthetics dilemma is that many of the features of dreams, if employed in the most obvious ways, undermine OSR play styles. Do you want surreal dream space, or do you want the spatial logic of the dungeon crawl? Do you want absurd causalities or lateral problem solving? Do you want NPCs to embody the aesthetics of mysterious symbolism or do you want coherent factions with hopes and dreams of their own? CHOOSE. You can't have both.

The Atkinson Hotel made this dilemma vivid for me. It consisted of a pointcrawl between eight hotel locations from a creepy turn of the (20th) Century hotel, connected by often surreal transitions. For example, the first room had a normal door that led (presumably) down a hallway to a ballroom, but also a door in the back of the closet that led to cramped storage room, and one under the bed that led straight into a hot tub in the hotel baths. Given its limited number of locations, it was clearly not a map of an actual hotel, but rather of dream scenes like one might have in a dream (nightmare) of the Hotel Atkinson.

This meant that there was no place for the hotel staff or other guests that you might meet to reside on the map. They existed just as encounters waiting to happen in fixed rooms, or as random encounters. Some of the inhabitants were just doing something in a room with no naturalistic connection to anyone else, like the 1 HD chefs in a kitchen which apparently served no one. When I ran this room, I constructed a vivid scene in the kitchen, treating them in my mind like Maurice Sendak’s ominous but not malicious bustling chefs from a favorite children’s book of mine, In the Night Kitchen—which by the way is clearly about an anxiety dream. The players grasped the chefs as the surreal obstacle that they were, engaging with them appropriately in that mode by staging a deliciously ridiculous distraction to get past them.

But afterwards they reported that this whole thing really cramped their agency. They couldn’t reason in naturalistic ways. They felt like when they closed the door on someone they would cease to exist. They felt that many of the people they met, like the chefs or even some of the guests were maybe not real people they could engage with in the open-ended ways they were used to dealing with NPCs and factions. They knew that they couldn’t really leverage the absurd space of the hotel. There wasn’t really a there there. This meant they couldn’t fully engage in OSR style play.

And by the way, I consider that a good adventure in the mode of embracing the surreal aesthetics of dreams. Hence the dilemma.

The Dilemma Dissolved

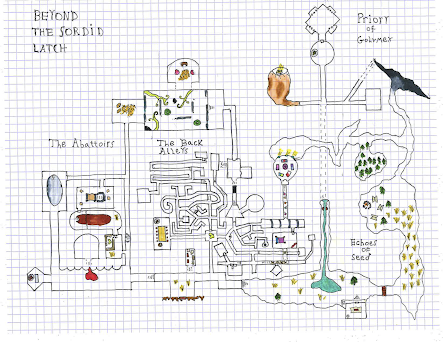

My view is that this dilemma can be overcome—that we needn’t choose between dreamy aesthetics and old school playstyles, but only if we learn how to capture dream aesthetics in ways that don’t disrupt the logics of OSR play. I have a lot of experience trying to do this, admittedly with varying degrees of success. My best attempt, in print, is probably The Ruins of the Inquisitor’s Theater from

Through Ultan’s Door 1. But there are some good dreamy bits in Through Ultan’s Door 3 as well, and many other unpublished things that I think worked fairly well in this vein from my long running (and now multiple) home games in Zyan.

The Surreal Adventure Location Premise

You can often get a lot of mileage by having a surreal premise for an adventure location, and then otherwise allow the adventure location to follow normal old school norms for exploration.

Here’s a dreamy premise for a locale: a theater where people are punished by puppets for being bad. Why is this dreamy? For one thing, it’s immediately recognizable as a child’s nightmare. Puppets are meant to entertain, and there is something sinister and dreamlike in reversing their function in this way. As dreams do, it also picks up on something real, something subtly alarming about puppets: their uncanny resemblance to humanity, and unnerving wooden theatricality.

In

Through Ultan’s Door 1, rather than developing this dreamy premise through vivid puppet scenes and symbolic elements from childhood, I instead did the location up as proper ruins for dungeon crawling purposes. I gave it a rationale, treating trial by puppet as a holy spectacle conducted by a religious order no longer present. Like all ruins in D&D, I had other factions who had crept in since then, who were occupying different parts of the dungeon and were in conflict with one another. In this way, I began with a surreal dreamy premise and then treated the space as a naturalistic environment in accordance with ordinary (old school) dungeon logics. I tried to capture a vivid sense of place in connection with surreal theme—but then I always do that when designing an adventure locale.

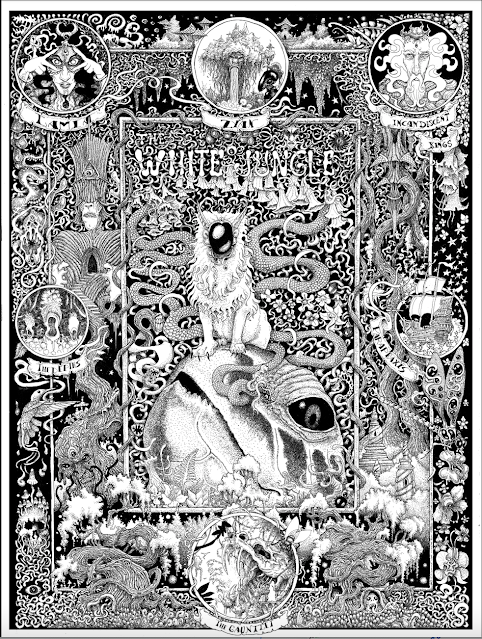

Or consider a hex crawl, another procedural space of exploration, this time wilderness exploration. A striking example from my home game that has yet to see print, except in Huargo’s deliciously lurid poster above, is the White Jungle. The concept of the White Jungle is simple: it’s a jungle but it’s upside down. This premise literally upends the ordinary orientation of waking life, where the ground is under your feet and the sky is above your head. It makes a place (a jungle) that is already surreal in its unimaginable vibrance of life an order of magnitude weirder.

Once you have that absurd dream premise, the key to old school exploration-based play is to treat it, from that point forward, as if it's a naturalistically intelligible location. The jungle is not a pretext for a series of disconnected vivid dreamlike scenes where common sense physics is turned upside down. It is a hexcrawl that hangs from the bottom of a flying island. The jungle is a real physical space player characters can explore, as if it were a real wilderness. Just like falling is a thing in the real word when you’re climbing around according to our invisible rulebooks, so falling will also have to be an ever-present possibility here. Since the jungle is vertical, I fit it to hexcrawl conventions by creating a series of stacked hexmaps to model its four different levels, with rules for both vertical and lateral travel.

Suppose we zoom out from the level of the dungeon or the wilderness crawl to the level of the world or setting. Generally speaking, if you’re going to have an entire campaign where PCs in the waking world somehow explore dream locales, my first advice would be to follow the dreamlands aesthetics of Lovecraft, or Lord Dunsany from whose superior notes he was cribbing. Treat the dreamlands as an actual place—a land—where adventures can be had. Then you can embed surreal premises in ordinary exploration enabling locales. In other words, don’t treat it as disconnected dream bubbles that vanish when the players exit. Let there be a real there there at all levels from adventure locales to the whole world—the country of dreams.

Although this is the approach I’ve taken, it’s far from the only one possible. I’ll talk about Johnstone Metzger’s

Nightmares Underneath a little bit later. It takes a different approach.

Jumbled Items, Conflated Locations, and Wonky Causes

Probably the single most dreamlike element from the White Jungle is the mysterious identity between the sky and the sea. The Zyanese call the sky, “The Endless Azure Sea”. The lowest level of the White Jungle is The Dangling Isles, where only a few groves descend into the depths of the Endless Azure Sea. They are like archipelago of inverted wooded isles, between which flying fish swim on the currents of air in the open sky. Of course, this strange environment is modeled in typical OSR fashion, by way of a hex crawl, and encounter tables populated by birds, flying fish, and other stranger aerial-aquatic beings like the immortal spirits of the air, the aery elemental demons of Wishery, or the painted baboons, dream travelers who skirt the lowest isles in hot air balloons. This phantasmagoria of dream elements is simply a hexcrawl with an associated encounter table, rules of travel, and the like.

The most dreamlike element in my Ruins of the Inquisitor’s Theater is probably the tree of silver melons. It grows in the darkness, with its roots in a loamy soil of decaying law books full of the casuistry and hermeneutics of the crooked law of Zyan. Having burst from the law library, its gnarled roots now block the door, its branches heavy in the darkness with silver skinned melons. These sweet, white-fleshed fruits have seeds like letters, so that if one is cut open, jumbled text can be seen. When one eats the fruit, one imbibes the knowledge from which the tree has nourished itself, becoming a fearsome Zyanese jurist.

There are many oneiric elements to this scene. A tree, heavy with silver-skinned fruit grows in the darkness: this already defies the laws of plant life. Its soil are books of the law, and the fruit somehow distilled their hermeneutics, so that when one eats the fruit, one somehow reads the books. Here we have the conflation of items typical of dream logic. Imagine describing a dream this way, “The fruit from the tree was somehow a book, and when I ate it, I was full of knowledge.” There is a strange identity of things, and causal logic breaks down.

And yet, when placed on the map, the tree is just a tree. Aside from its absurd implied cycle of life, it operates according to invisible rule books. For example, one must cut through the roots to reach the blocked door to the law library. Although fresh wood, it still could be used to try to kindle a fire.

Even the fruit can be assimilated to the challenge-based logics of old school play. In old school play, as I’ve written elsewhere, magical items are less passive buffs to characters (+1, +4, resistance to damage, etc.) and more like strange and very specific tools that players may use in unpredictable ways for out of the box problem-solving purposes. (An activity Ben Milton charmingly calls

“shenanigans”.) For all their lurid dreamlike properties, the melons of the tree are essentially magic items—in D&D parlance, they are potions. In my new face to face game, where the party recently found this tree, I decided that the fruit would have a 24-hour duration, which assimilated them further to the logic of old school one use magical items. They are a resource the party can now deploy in unpredictable to solve their problems with an entirely new means: through superb legal reasoning. God only knows to what use they’ll put this strangely specific skeleton key—which is just how I like it.

The Secret Dream Logic of Dungeons and Dragons

Earlier my advice was to fit dreamy premises into standard modes of procedural exploration with their ordinary(ish) spatial logics and standard issue invisible rulebooks. In other words, my advice was to tame dream elements for old school play by embedding them in tried and true exploration formats. Good advice, I think. But the tree of the law hints at more interesting possibilities. How to describe what happened with the tree and its fruits to allow this synergy between dream aesthetics and old school play styles?

What I did with the tree, I think, was lean into what we might think of as the latent dream logic of dungeons and dragons. This dream logic is obscured by the accretion of decades of workaday publishing and tiresome tropes. It’s hard to see it Gary’s encyclopedic treatment and decades of late TSR and WoTC cruft. Let’s stick for the moment with the “potion” framework. Take the most quotidian of potions: the potion of invisibility. Let me redescribe it, adding just a little bit of aesthetic flare, as if it were a dream element.

“I drank a liquid so clear I couldn’t even see it was there. And when it was in me, somehow no one could see me. I could watch people, but not interact with them. I knew that if I did, they would see me and they could hurt me.”

There is a lot of dream thinking already happening in the formats for adventure locations and items, bog standard as they might seem. In fact, even procedures of exploration are dreamlike when thought of the right way. In Original D&D, the megadungeon around which play was assumed to center had exacting exploration rules that intensified the peril of dungeon delving, forced resource management on players, and generally titled things against the PCs. All monsters could see in the dark, but no PCs could. Light sources would deplete and flicker out. All doors were stuck for PCs and would close behind them, needing to be forced open--but yet they would open freely for monsters. I’m going to quote

Philotomy’s wonderful explanation of these exploration procedures enabling high stakes old school dungeon exploration at length.

There are many interpretations of "the dungeon" in D&D. OD&D, in particular, lends itself to a certain type of dungeon that is often called a "megadungeon" and that I usually refer to as "the underworld." There is a school of thought on dungeons that says they should have been built with a distinct purpose, should "make sense" as far as the inhabitants and their ecology, and shouldn't necessarily be the centerpiece of the game (after all, the Mines of Moria were just a place to get through). None of that need be true for a megadungeon underworld. There might be a reason the dungeon exists, but there might not; it might simply be. It certainly can, and perhaps should, be the centerpiece of the game. As for ecology, a megadungeon should have a certain amount of verisimilitude and internal consistency, but it is an underworld: a place where the normal laws of reality may not apply, and may be bent, warped, or broken. Not merely an underground site or a lair, not sane, the underworld gnaws on the physical world like some chaotic cancer. It is inimical to men; the dungeon, itself, opposes and obstructs the adventurers brave enough to explore it. For example, consider the OD&D approach to doors and to vision in the underworld: Generally, doors will not open by turning the handle or by a push. Doors must be forced open by strength...Most doors will automatically close, despite the difficulty in opening them. Doors will automatically open for monsters, unless they are held shut against them by characters. Doors can be wedged open by means of spikes, but there is a one-third chance (die 5-6) that the spike will slip and the door will shut...In the underworld some light source or an infravision spell must be used. Torches, lanterns, and magic swords will illuminate the way, but they also allow monsters to "see" the users so that monsters will never be surprised unless coming through a door. Also, torches can be blown out by a strong gust of wind. Monsters are assumed to have permanent infravision as long as they are not serving some character. (The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures, pg 9)What Philotomy does in this passage is link exploration procedures that make dungeon exploration challenging and fraught to a certain idea of what a dungeon is, which he calls, following OD&D, the "Underworld”. Note what he does and doesn’t say about the Underworld. The Underworld has an ecology, “a certain amount of verisimilitude and internal consistency”, that allows one to reason about it in ordinary ways, or where it departs from the ordinary, to puzzle out its general principles of operation. Although it has its own ecologies, and mappable spatial logics, the mythical underworld is somehow opposed in its nature to adventures. Philotomy invites us to view the rules about stuck and closing doors, or light sources and vision, not only as artificial game elements that make high tension procedural exploration possible, but as the metaphysical expression of a place that “gnaws on the physical world like some chaotic cancer”. In other words, Philotomy takes the idea of a megadungeon as the center of a campaign, and associated exploration mechanics, and following the lead of the OD&D rulebooks, invites us to view “the dungeon” as an inimical dream space, surreal in parts, where the laws of reality above may not apply. It is as if a dream has broken through into reality, and the exploration rules about stuck doors are an exploration of the way in which the whole thing is like a living nightmare.

Although I can’t do it justice here, Johnstone Metzger’s

The Nightmare Underneath runs with this idea in the best possible way. In a high Islamic setting dominated by reason, law, and civilization, “the nightmares underneath” are breaking through in the dungeons the setting calls “nightmare incursions”. Metzger recasts traditional rules for exploration of perilous spaces through the nightmare metaphysics of this reimagined Underworld. Dispensing with the idea of a megadungeon, he opts for smaller adventure locales that nonetheless adhere to the logic of the “Underworld”, now explicitly rationalized as an expression of the incursion of nightmares of unreason into the orderly world of law. He also introduces novel exploration rules that have to do with the nightmare being at the heart of the incursion. Brilliantly, he does this too with the idea of PC party as rootless, social outsiders, a common and often derided trope from early D&D. In The Nightmares Underneath, the PCs are adventurers who for unknown reasons are able to enter these nightmare incursions without being destroyed. They are in some ways pariahs outside of the civilization, although civilization depends on them as a dubious cure for the chaotic cancer that gnaws at reality. He also recasts the idea of dungeon exploration as treasure hunting, by having each nightmare incursion held in place by an “anchor”, a valuable piece of treasure to which the nightmare incursion is tied. (This allows him to reinterpret the idea of treasure for XP, in a way that fits with the dungeon as a nightmare space: to cut out the cancer of the incursion one must remove the treasure that “anchors” the nightmare from the dungeon.) In short, Metzger runs with the idea of the Underworld reimagining rules and setting tropes in relation to his recasting of the Underworld as a literal nightmare, while pleasingly subverting their original meanings.

Even without going as far as Metzger does to aesthetically reimagine the entire game this way, we can see many discrete elements in Dungeons & Dragons that are amenable to this kind of treatment. Take, for example, another trope of D&D in its many incarnations: the “funhouse dungeon”. Here we have a dungeon with a feel of a funhouse. Surreal elements jostle with one another in close proximity, defying the tidy confines of our daytime expectations. One might find here hellish games of chance alongside bizarre traps, riddling manticores, and other monsters implausibly occupying single rooms. Funhouse dungeons rightly get a bad rap in part because they push against the logics that enable unscripted exploration-based play. Why would real factions with lives of their own sit waiting in a room down the hall from a demonic circus barker (or whatever)? The danger is that the whole thing becomes like the Hotel Atkinson, a series of vivid but discrete scenes, rather than an open-world environment that can meaningfully be navigated. But before we dismiss the funhouse dungeon, perhaps we could pause a moment to acknowledge what a glorious fever-dream it is. There are ways of reimagining a funhouse dungeon to keep the demonic circus barkers and cannibalistic manticores, while enabling OSR playstyle. We should consider the funhouse dungeon as a surreal resource in D&D on which to draw. And there are a million things that are like this, from potions, to talking swords, alignment languages, travel by silver chord in the astral plane, and much more.

In other words, I’m saying that if we wish to embody dream aesthetics in our games, we might go beyond embedding a dreamlike premise in tried and true exploration structures. We can do more than paint an oneiric glaze on established Dungeons & Dragons tropes. There’s a lot that’s surreal in the history and practice of D&D. Why not intensify the dreamlike (il)logics implicit in otherwise stale D&D tropes and exploration mechanics? We can make things fresh by awakening the dream aesthetics that already slumber just below the surface of the game. Like Metzger, we can reimagine the entire system of rules and tropes as expressive of dream aesthetics, or otherwise rationalized by them. Or we can do it in a more piecemeal fashion.

In closing, what I want to say is that we can do both of these things. We can place dreamlike premises that conflate places, render objects ambiguous, or apply a single surreal twist, in tried and true exploration frameworks. This is to treat them as real place, or real factions, that allow for challenge-based, exploration, sandbox play. Or, we can work to bring out the dreaminess of those very exploration frameworks or seemingly workaday tropes of what is already an absurd game. To bring out the dream aesthetics, we just need to own the absurdity.

.png)